The Giver is one of those books I really, really should have read a long time but never got around to it. When it was released in 1993 I was already a teenager and there was no way in hell my school district was going to put it on the reading list so, unlike many fans of the work, I wasn’t aware of the story as a child. But it’s never too late to read a classic, and I have to say I enjoyed the book even though I’m far beyond the age of the target audience.

The book exposes us to the future world of Jonas, a soon-to-be twelve-year-old boy in a community that seems perfect at first. Everyone gets along. There are no wars, no crime, no fights, no unemployment. Everyone is fed, children have loving homes, and the elderly are respected and taken care of. But it all comes at a terrible cost, as the “Sameness” that brought this peace also drains the community of what we consider the joys of life, and love.

I won’t call this a dystopian novel, because the world it portrays isn’t necessarily a horrible one. It’s just very different. Jonas is not genetically related to his parents and sister; he was given to his parents after he was birthed by a designated birth mother, as all children in the Community are. His parents don’t even have sex. No one in the Community does. It is a culture marked by sterilization and predictability. But, initially, this doesn’t seem particularly insidious. There are actually some ideas that seem great on the surface. Family units (that’s actually what they’re called) in the community talk about their feelings to each other. It creates an environment where things are shared openly. Young children in the Community wear jackets that button up in the back so that others must help them dress; this creates a sense of community interdependence, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s only when you learn that these things are required by the powers that be, and adherence to The Rules is closely monitored, that these ideas become dark and foreboding. You can easily see how these concepts might have started with the best intentions but evolved into a system that snuffed out personal freedom. But, for the most part, the people in the community live safely and soundly, and since we’re not given a complete view of the world outside, it’s hard to say that The Community setup wasn’t borne out of necessity in a world that was going mad.

The other element that adds a sense of wrongness to the world is the concept of “release” from the community, which usually happens when people reach advanced age, but rarely is used as punishment and even more rarely used when infants don’t develop as healthy as The Community dictates is required. For the sake of a spoiler-free review, I won’t go into detail here. But when reading the book, I think most adult readers could easily come to a conclusion about what was really going on. There are no real plot twists in this book, but if you read it as a kid you might have been surprised, just as Jonas was. And that’s the beauty of the book, really; the end of childish naivete through knowledge. This theme kicks into full gear when Jonas meets The Giver, the only caretaker of memories from the past world, before The Community system whitewashed everything in the pursuit of perfection.

Still, the young age of the protagonist was a key factor in what made the story’s themes so powerful. Jonas just turned 12, yet The Community deems that to be the age where all citizens enter adulthood and assigned the careers they’ll have for the rest of their lives. This concept works because on one hand, it does make a bit of sense, but on the other hand it completely disregards the maturation process between the teenage years and adulthood. It’s a concept that seems alien and wrong, but for The Community it is normalcy.

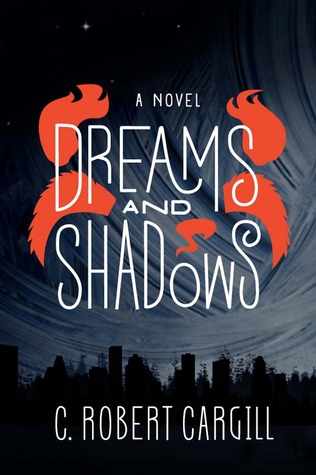

That’s why I was disappointed to learn that the upcoming movie version of The Giver increased the ages of Jonas and his friends from 11/12, to 16. There’s a world of difference between those pre-teen years and mid-teens, and it seems like the entire tone of the story would change and lose much of its magic. But I will refrain from judging until the movie comes out, and with Oscar award winning cast members like Meryl Streep and Jeff Bridges there’s a chance the movie will still be good (although the movie also has Taylor Swift cast, which should be…interesting).

I’m sure there will soon be much media attention given to this story because of the film, but I encourage everyone to read the book first (and it’s a short, easy read). The Giver is a well-crafted book that took a bold approach of introducing difficult and challenging societal concepts to kids. It’s the kind of thought-provoking modern literature that teaches lessons relevant to today’s world. It’s meant for kids, but adults can certainly get something out of it as well.